Introduction

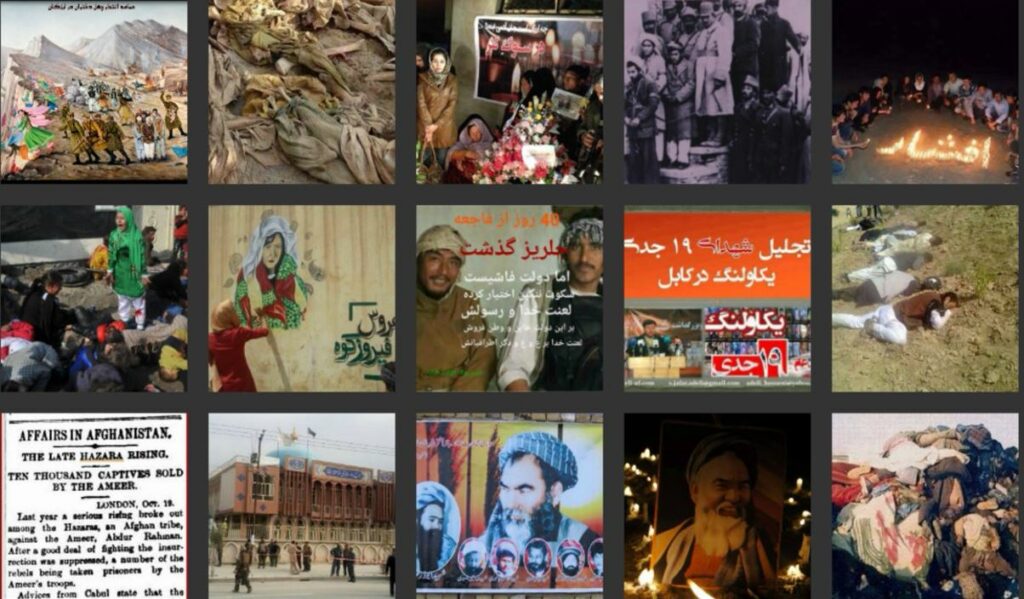

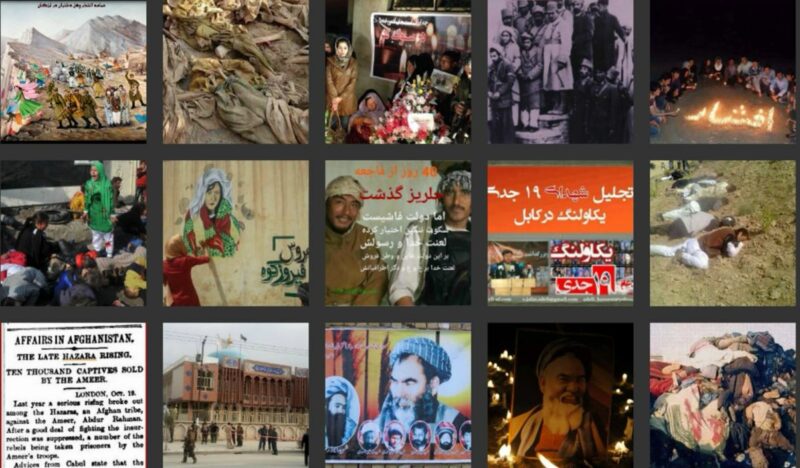

Among the many tragedies of modern and pre-modern history, the plight of the Hazara people stands as one of the least recognized yet most persistent. Often referred to as the “forgotten victims” of ethnic persecution, the Hazara community has endured centuries of systematic violence, marginalization, and attempts at eradication. While the term “genocide” carries weighty legal and moral significance, the cumulative evidence of massacres, forced displacement, discrimination, and targeted killings strongly supports the claim that the Hazara people have been and continue to be subjected to genocidal practices.

This article seeks to provide an in-depth examination of the Hazara genocide: its historical roots, the mechanisms of oppression, its continuation into the 21st century, and the ongoing calls for recognition and justice.

Who Are the Hazaras?

The Hazaras are an ethnoreligious minority, primarily residing in central Afghanistan—an area historically known as Hazarajat—with diasporic communities in Pakistan, Iran, and beyond. They are distinct for several reasons:

- Ethnic Identity: Hazaras are believed to be of Mongol-Turkic descent, with physical features that often distinguish them from Afghanistan’s dominant Pashtun and Tajik groups.

- Religion: The majority of Hazaras are Shia Muslims, in a country where Sunni Islam is the majority faith.

- Cultural Markers: They speak Hazaragi, a Persian dialect, and have unique cultural traditions.

These differences—religious, cultural, and physical—have historically marked them as “outsiders” within their own country, rendering them targets of systemic prejudice.

- More information on Bolaq Hazara Genocide Archive

Historical Roots of Persecution

19th Century Campaigns under Abdur Rahman Khan

The most devastating early wave of violence against the Hazaras occurred in the late 19th century under the rule of Emir Abdur Rahman Khan.

- In the 1890s, Abdur Rahman launched a brutal campaign against the Hazaras, motivated by both sectarian zeal and political consolidation.

- Thousands of Hazaras were massacred; estimates suggest that between 50–60% of the Hazara population was exterminated.

- Survivors were enslaved, forcibly displaced, or dispossessed of their lands, which were redistributed to Pashtun tribes loyal to the Emir.

- Women and children were sold in slave markets, marking one of the darkest episodes in Afghan history.

This campaign not only decimated the Hazara population but also entrenched their position as a marginalized underclass in Afghan society.

20th Century Patterns of Marginalization

While no single campaign of extermination matched the brutality of Abdur Rahman’s reign, the 20th century was marked by entrenched systemic discrimination:

- Landlessness: Many Hazaras were reduced to tenant farming or sharecropping, dependent on landlords from dominant ethnic groups.

- Exclusion from Power: They were excluded from political institutions, the military, and education.

- Cultural Stigmatization: Hazara identity was often associated with servitude, backwardness, and inferiority in Afghan social hierarchies.

Though moments of relative tolerance appeared—particularly during the monarchy in mid-20th century—systematic barriers remained.

The Hazara Experience During Modern Conflicts

The Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989)

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and subsequent resistance reshaped Afghan politics, but for Hazaras, it was a double-edged sword.

- In Hazarajat, local Shia militias emerged, supported by Iran, providing the community with some degree of autonomy.

- However, the broader war environment worsened inter-ethnic violence and fueled new sectarian hostilities.

The Afghan Civil War (1990s)

The early 1990s civil war following the Soviet withdrawal once again brought devastation.

- Hazara political groups, particularly Hezb-e Wahdat, vied for power in Kabul.

- In 1993, the Afshar massacre unfolded, when forces loyal to Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf attacked Hazara civilians in Kabul, killing hundreds and committing atrocities including sexual violence.

This event reinforced the vulnerability of Hazaras even within multi-factional struggles.

Taliban Rule (1996–2001)

Perhaps the starkest case of genocidal violence against Hazaras in modern memory occurred under the Taliban regime.

- Mazar-i-Sharif Massacre (1998): After capturing the northern city, Taliban forces carried out mass killings of Hazaras. Human Rights Watch estimated that between 2,000 and 5,000 civilians were killed in a matter of days while various accounts claim the death toll to be between 10,000 to 15,000 people.Witnesses reported systematic targeting, door-to-door executions, and the infamous command attributed to Taliban leader Mullah Niazi: “Hazaras are not Muslims. You can kill them. It is not a sin.”

- Bamiyan Atrocities: In central Afghanistan, Taliban campaigns devastated Hazara communities, including the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, which many scholars interpret not only as an attack on cultural heritage but also as a symbolic assault on Hazara identity.

The Taliban’s sectarian ideology, blending Deobandi-Sunni extremism with anti-Shia fervor, framed Hazaras as legitimate targets for extermination.

The Post-2001 Period: Persistence of Violence

The U.S.-led intervention in 2001 toppled the Taliban, and Hazaras initially experienced a resurgence in civil and political life. They gained representation in parliament, access to education, and visibility in professions previously closed to them. However, this revival was shadowed by ongoing violence.

Sectarian Attacks

- Militant groups, including the Taliban and later ISIS-K, have repeatedly targeted Hazara neighborhoods, schools, mosques, and community centers.

- Suicide bombings in Kabul’s Dasht-e-Barchi district—a Hazara enclave—have become disturbingly frequent.

- Schools such as the Abdul Rahim Shaheed High School (2022) and the Kaj Education Center (2022) were attacked, with dozens of Hazara students, mostly girls, killed.

Structural Discrimination

Despite some progress, Hazara communities remain underrepresented in national leadership and disproportionately affected by poverty and displacement.

The Hazara Genocide in Pakistan

Beyond Afghanistan, Hazara communities in Quetta, Pakistan have faced relentless violence since the early 2000s.

- Militant groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Sipah-e-Sahaba have carried out systematic attacks.

- Targeted killings, suicide bombings, and massacres at Hazara businesses and religious sites have killed thousands.

- The Hazara population in Quetta now lives in heavily fortified enclaves, effectively under siege.

This transnational dimension underscores the broader regional dynamics of sectarian hatred.

Why “Genocide”?

The UN Genocide Convention (1948) defines genocide as acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. The acts include: killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, inflicting conditions calculated to destroy the group, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children.

Applying this definition:

- Killing: Documented massacres from Abdur Rahman Khan’s campaigns to Taliban and ISIS atrocities.

- Bodily and Mental Harm: Suicide bombings, sexual violence, enslavement, and psychological terror.

- Inflicting Destructive Conditions: Forced displacement, economic exclusion, and ghettoization (e.g., in Quetta).

- Intent: Explicit calls by leaders, such as Taliban statements labeling Hazaras “infidels,” reflect genocidal intent.

Thus, the cumulative historical and contemporary evidence strongly qualifies the treatment of Hazaras as genocide.

International Response and Recognition

Despite overwhelming evidence, international recognition has been slow and inconsistent.

- Human Rights Organizations: Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have documented Hazara massacres, but often stop short of using the term “genocide.”

- Diaspora Advocacy: Hazara activists worldwide have campaigned for recognition, particularly in Europe, Australia, and North America.

- Recent Developments: In 2022, the UK Parliament formally recognized atrocities against Hazaras as genocide. Other governments and international bodies, however, remain hesitant.

The lack of robust recognition contributes to the continuation of violence, as perpetrators operate with impunity.

Hazara Resistance and Resilience

Despite centuries of persecution, the Hazara community has demonstrated remarkable resilience.

- Education: Hazaras have embraced education as a pathway to empowerment, producing prominent scholars, activists, and professionals.

- Political Mobilization: Leaders and organizations like Hezb-e Wahdat and later civil society groups have sought to represent Hazara interests in national politics.

- Diaspora Advocacy: Hazara communities abroad play an essential role in raising awareness, organizing protests, and lobbying governments.

- Cultural Preservation: Through literature, music, and art, Hazaras continue to assert their identity against forces of erasure.

Challenges Ahead

The future of the Hazara community remains uncertain, with several challenges:

- Resurgent Taliban Rule (2021–present): Since the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan, attacks on Hazaras have persisted, raising fears of renewed large-scale massacres.

- ISIS-K Threat: ISIS-K’s virulent anti-Shia ideology poses an existential danger to Hazara civilians.

- International Neglect: The world’s focus on geopolitical rivalries and broader Afghan crises often sidelines Hazara-specific issues.

- Refugee Vulnerability: Hazaras fleeing violence face precarious conditions as refugees and asylum seekers, with limited international support.

Toward Justice and Recognition

To address the Hazara genocide, several steps are crucial:

- Formal Recognition: Governments and international organizations must acknowledge the atrocities as genocide.

- Accountability Mechanisms: War crimes tribunals and sanctions against perpetrators are necessary to break cycles of impunity.

- Protection Measures: International agencies must prioritize Hazara neighborhoods, schools, and places of worship for humanitarian protection.

- Support for Refugees: Host countries should provide asylum pathways and protections for Hazara refugees.

- Amplifying Voices: Hazara voices—writers, activists, survivors—must be centered in conversations about their future.

Conclusion

The story of the Hazara people is one of immense suffering, but also of profound resilience. From the massacres of the 19th century to the suicide bombings of today, the Hazaras have borne the brunt of ethnic and sectarian hatred in Afghanistan and beyond. To call their experience a genocide is not merely a semantic choice; it is a moral imperative. Recognition is the first step toward justice, but it must be followed by concrete action to ensure their survival and dignity.

For too long, the Hazara genocide has been a silent crisis. The international community can no longer afford silence. The survival of one of the world’s most persecuted peoples depends on awareness, recognition, and solidarity.