After almost 20 tough years, the United States has realized it needs to rethink the political structure in Afghanistan or the state as a whole since it has failed to preserve a social contract. Or, looking at the scenario, it would be appropriate to say it was never the intention to build the Afghan state on a social contract. Rather, it was formed through international intervention as an exogenous project, overlooking, and in certain cases neglecting, the realities of Afghan society. The first Afghan constitution that was framed in the United States’ state-building project in Afghanistan and launched through the Loya Jirga in early 2004 set the stage for all the mayhem that was to follow. A highly centralized presidential system, with a unitary character, disregarded the heterogeneous nature of Afghan society, made a mockery of its historical and cultural reality, and paved the way for ethnic tensions. But the plan had to fail and the reality had to take its revenge, and so it has, and now all the stakeholders seem bewildered, having no idea of what to do next.

Where does the Afghan state stand? Well, it is ranked as highly fragile, with serious challenges to peace and stability. As per the Fragile State Index 2020, Afghanistan’s score is 102.9, which is 9th in the world, among 178 countries. The indicators that show serious concerns are Security Apparatus, Public Services, Refugees and IDPs, State Legitimacy, and Factionalized Elite. Security apparatus remains incapable to deal with several dozen terrorist groups still active in the country. Among the most prominent ones are Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP) or Daesh and Al-Qaeda, which is believed to have members from both “AQ Core” group and its regional affiliate Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and have links with both Afghan Taliban and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Daesh is notorious for its lethal sectarian attacks on civilians, like attacks on mosques, shrines, marriage halls, education centers and even hospitals in the capital Kabul; particularly, targeting Shia Hazaras and willfully victimizing their women and children, in the western suburbs of the city.

Public services are difficult to be found as public institutions remain weak and incapable to deliver anything worthwhile. The result is that poverty has climbed to a staggering 72 percent, and unemployment has reached to 40 percent; while, 13.15 million people suffer from acute shortage of food. Refugees and IDPs struggle to return to their abodes as there is no mechanism to make that possible. Incapacity to provide security, justice and rudimentary requirements of life has further thinned state legitimacy that is suffering from divisions and ethnic strife prevalent among the ruling elite.

What has been the cost of these ‘achievements’? The U.S. alone has spent around $2 trillion for the war in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2019. Besides, the U.S. foreign aid for Afghanistan has totaled $18.8 billion since 2001. In addition, the human cost of war in Afghanistan, during the same period, has been alarmingly high. Data show that 43,074 civilians have been killed in the country and many others have been injured or badly influenced by insecurity. Meanwhile, the number of U.S. military casualties is estimated to be around 2,298, and that of U.S. contractors is around 3,814. The cost-benefit analysis from the given numbers is not difficult at all; however, it is unfortunate to find that the policy makers have learnt minimum, and the stakeholders remain tight to their own interests.

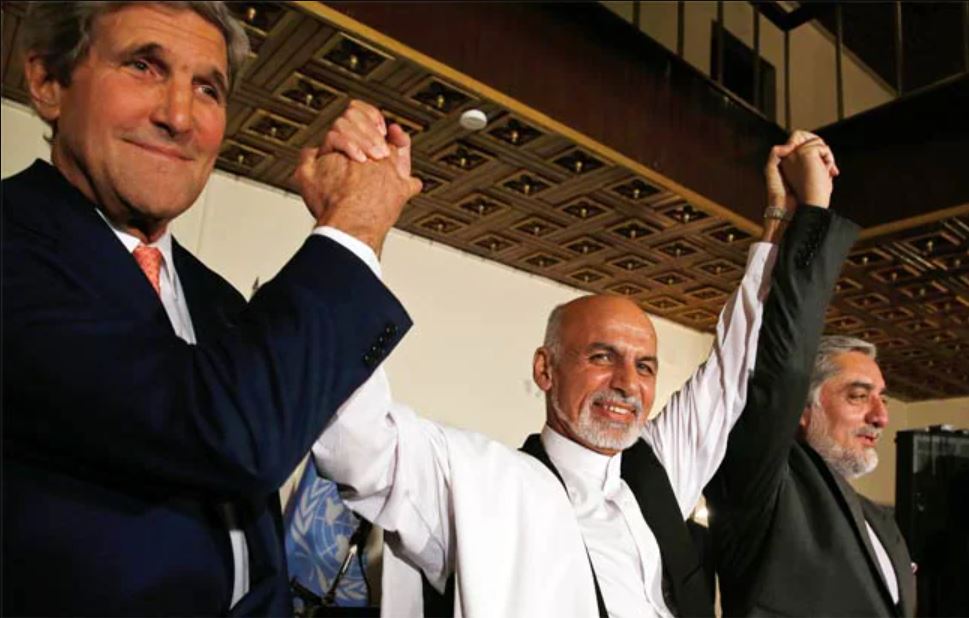

The lengthy U.S. intervention in Afghanistan has not achieved even a viable peace process, let alone the ambitious state-building initiatives. As U.S. President Joe Biden has announced to withdraw troops from Afghanistan by September this year, the prospects of peace in the country remain dim. The U.S.-Taliban deal, not clear whether applicable anymore, has only brought the Taliban at a point where they have rejected peace talks in the presence of foreign troops in Afghanistan. On the other hand, the talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government representatives are not possible as the Taliban consider President Ghani’s government as a ‘puppet’. To make the matter worse, the Ghani administration is not considered legitimate by some prominent political figures and warlords who are part and parcel of the Afghan elite and favor the republican system in the country as opposed to Shariah-based rule proposed by the Taliban. They even accuse Ghani of ethnic discrimination, as the vital positions within his cabinet are occupied by Pashtuns, while Tajik, Hazaras and Uzbeks are sidelined. And, a highly centralized political system and presidency has entertained him in his arrangements. Therefore, we can say there are divisions among divisions within Afghan political elite, and the Afghan state has further deteriorated the rifts instead of providing any binding force.

In such a complex scenario, any optimism about achieving something worthwhile from Istanbul Conference, if ever organized, remains misplaced, though Afghan elite, under the High Council of National Reconciliation (HCNR), had already prepared to discuss the future of the Afghan state, and had even chalked out a plan. But, they need to realize that, in the current scenario, getting their blueprint accepted through a conference or summit is nothing more than a daydream. Maximum achievement from the ongoing peace process would be ensuring a lasting ceasefire, a transitional government and surety to secure a ‘republican’ system as opposed to a theocracy or a Shariah-based rule. However, a lasting peace-building project requires comprehensive state-building efforts based on the prevailing socio-political realities. Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic and multi-sectarian tribal society, with informal, traditional and local bases of legitimacy. A unitary form of government, with highly centralized administration, has never been able to serve the social contract in the country. Neither can a centralized setup based on Taliban’s version of Shariah serve the purpose. Only a decentralized, federal system, with a capable local government, can preserve a social contract based on the rights of self-governance to different ethnic and sectarian groups, and a guarantee of stable, effective and legitimate state.