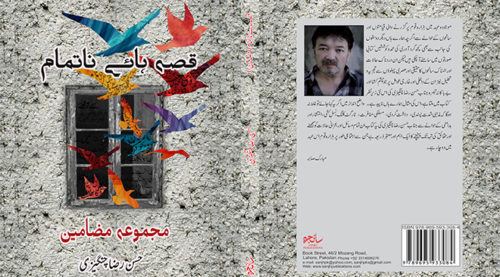

The book is a collection of Hasan Riza Changezi’s articles most of which were published in the Dawn newspaper as Urdu language blogs. The book contains thirty-one of his selected articles written during the horrific period of 2012-2015 when Pakistan in general and Quetta in particular, was ablaze with sectarian terrorism. The writer has highlighted the socio-economic and political situation of Pakistan which rendered the country to become a hell for minority communities.

The writer has expressed his disdain for human rights abuses of all ethnic and religious communities. He condemns extrajudicial killings and dumping of the mutilated bodies of Baloch activists in Balochistan, killings and forced conversion of young Hindu girls by fanatics, merciless massacres of Shia, Ahmadi and Christian communities in Pakistan. However, the writer seems to be deeply affected by the prevailing environment of terror in his own neighborhood. Readers will find the tale of Hazara genocide at the heart of this book, frequently finding Changezi’s arguments and protests against the ills of the Pakistani society and is critical in his take on state institutions in an activist’s attempt to bring an end to the sufferings of his people.

Hasan Riza Changezi belongs to Pakistan’s Hazara community. The community, estimated to be 600,000 to 700,000 strong, is predominantly settled in the two urban townships of Marriabad and Hazara Town in the provincial capital of the insurgency riddled Balochistan province with some settlements in Karachi and Islamabad. They are predominantly adherents of the Shia denomination of Islam and their mongoloid facial features distinguish them from the rest of the Pakistani citizens. This physical specification has rendered them an easy prey to attacks by the terrorist groups across Pakistan.

In the last chapter of his book, the writer quotes statistics collected by Hazara Organization for Peace & Equality (HOPE) on targeted attacks on the Hazaras. According to HOPE, around 1400 Hazaras have been killed and over 3500 wounded in a series of 158 separate attacks in and around Quetta city. However, the merciless killings of the community members continued unabatedly since the article was written. The current statistics of the organization shows that the total numbers of the Hazaras killed and wounded are much higher.

The articles incorporated in this book recount tactics adopted by the terrorist groups aimed at maximising the number of fatalities. They have conducted suicide attacks in public spaces such as markets, mosques, sports clubs and even hospitals. They have shelled graveyards in which the Hazaras were burying their dead that had fallen victims to terrorist attacks. The terrorists have struck the Hazara students going to their universities and the Hazara government officials and business people en route to their jobs. Most tragically, the militants have singled out Hazara passengers from the public buses on three main occasions, taken them off, lined them up and executed them while filming the whole incident.

The responsibilities of the attacks on the community were accepted by Lashkar-e Jhangvi and Jaish-ul Islam terrorist outfits.

Hasan Riza Changezi traces back the history of religious militancy in Pakistan to three main changing political dynamics in the region during the cold war era. The Islamization of Pakistani State by General Zia-ul Haq who deposed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in a military coup sanctioned by the US, the West and the Arab world. The establishment of the Pro- Russia communist government by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan as a result of the April 1978 military coup, also known as the Sawr Revolution (the month in which it was launched) which was a matter of grave concern for Pakistan’s military dictator General Zia, the United States and the Arab monarchs. The Arab world in particular was concerned with the establishment of a Shia theocracy, Velâyat-e Faqih, as a result of the Islamic revolution in 1979 by Khomeini, ending monarchy in Iran.

Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the US with its Western allies sponsored jihad (holy war) against the Soviet Union. Zealous Muslim fighters rallied to seek training and fight the communist government in Kabul. Pakistani intelligence agencies formed many Jihadist organizations with the help of Saudi money and provided free hands to Saudi Arabia to stretch vast numbers of religious seminaries to produce generations of jihadists to fight Pakistan and Saudi Arabia’s proxy wars in the region. On the other hand, Iran in order to export its brand of revolution and fight the communist regime, formed a number of its militant proxies in Afghanistan. Simultaneously Iran in order to counter Saudi Arabia’s influence in Pakistan formed Tahreek Nifaz-e-Fiqh-e-Jafaria (TNFJ), a Shia organization that launched a movement to implement Shia jurisprudence in a Sunni majority country in July 1985. The nationwide protest on July 6th, 1985 marked the first show of power by TNFJ, which alarmed Pakistan’s military dictator and his Arab allies.

General Zia-ul Haq crushed the movement but the event proved to be a turning point in the history of sectarian militancy in Pakistan. Within days, Sipah-e Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) came into being with tangible support of Saudi Arabia. Both TNFJ and SSP commenced sectarian conflict by targeting each other’s top leadership. Allama Ahsan Ellahi Zaheer was the first victim of sectarian killings. He was said to be from Ahle Hadith cult who was killed in a bomb blast in 1987. He was known for his stance against other groups in Sunni Islam and the Ahmadiyyah, and particularly against the Shias who he considered to be infidels. In retaliation, SSP killed Arif Hussein al-Husseini in Peshawar in Feb 1988. Later we witnessed the killings of people on sectarian ground across the Punjab, Sindh and KPK provinces of Pakistan which engulfed the lives of many individuals from different walks of life including some top professionals. Sipah-e-Mohammad and Lashkar-e Jhangvi emerged as an offshoot of the TNFJ and SSP at later stages to perpetrate killings of innocent human beings in the Punjab province. The era can truly be marked in the history of the country where for the first time, religion was used for political purposes. Sectarian fault lines and religious sentiments of the people were utilized to gain economic and political objectives.

According to the writer, in 1997 when Shahbaz Sharif became the Chief Minister of the Punjab, he signed a deal with the Lashkar Jhangvi to cease their operation in that specific province. The number of sectarian incidents was greatly reduced in the Punjab but sectarian violence started in Balochistan and other parts of Pakistan. Hazara Provincial Minister Sardar Nisar Ali, his guard and his driver became the first victims of sectarian attack in 1999. A Punjab based Lashkar Jhangvi (LeJ) operative was involved in this attack who had traveled from the Punjab to execute this operation. Since then, LeJ has claimed responsibility for the bulk of the attacks against the Hazaras.

Taking a glance at the statistics collected by HOPE, it can be concluded that attacks on Hazaras were reinforced in the wake of toppling down of the Taliban government by the USA and international coalition coupled with the rise of Baloch insurgency in 2003. On the one hand, the region became a safe sanctuary for global terrorists who fled from Afghanistan and on the other hand, Pakistani establishment set free terrorists to wreaked havoc on sectarian grounds to counter Baloch insurgency. Altogether, these policies jeopardized the very existence of Hazara community and other religious minorities in the province. Key leaders of LeJ, Usman Saifullah Kurd and Shafiq Rind, who were captured and sentenced to death by a counter-terrorist tribunal on November 8, 2003 in Quetta, managed to escape from a high security prison in 2008. It is worth highlighting that entry to and exit from that prison is not possible without a special security pass.

The writer does not ignore the role of pro-Iran Shia sectarian organizations that with the tacit support of Pakistani establishment left no stone unturned in perpetuating sectarian hatred by mobilizing people to attend protests and rallies sanctioned by Iran. The writer recalls the sobbing of those mothers, sisters, and children who lost their loved ones in different terrorist incidents which influence the writer to ask tough questions from those who were responsible for organizing Quds Day (Iran has designated the last Friday of the month of Ramadan as Quds or Jerusalem Day to draw attention to Israel’s policies towards the Palestinans.) in 2010 in Quetta, which was attacked by the terrorists belonging to the banned Lashkar-e Jhangvi claiming the lives of 100 innocent civilians who were lured by the pro-Iran Shia mullahs. The writer gives an eye witness account of the development of a sectarian atmosphere which makes the book a valuable addition for the study of Shia sectarian militancy in Quetta, that is rarely talked about.

The book is a unique document for the researchers working on the impact of militancy and terrorism on the Hazara community in Quetta. Changezi like a local storyteller gives an eyewitness account of the situation in which the Hazara community lived in peace and harmony in Quetta city. He recalls his youth when he was hanging around for pleasure with his friends who were neither Shia nor Sunni but, friends. The writer gives some first-person account of the situation in which sectarian hatred was induced in the minds of innocent people by both Shia and Sunni extremists in Quetta and turned the city into hell for its residents.

Like Changezi’s other intellectual contributions which include his translation of the “History of Hazara Mughul” written by Taimur Khanov and his co-authored work with Qais “Bisat-e-Shatranj” (The Geo-Political Chessboard), I recommend his collection of opinion articles “Qissa-hai-Natamam” (The Unfinished Stories) to my family and friends. It is their contemporary history in Pakistan which is unfortunately fraught with massive human rights abuses perpetrated against them in the last one and half decades. The book helps to understand the causes and effects of sectarian militancy on society and it gives a perspective on how to fight the menace of fundamentalism, extremism, and terrorism to ensure a peaceful co-existence for them in a diverse Pakistani society.

Hassan Riza Changezi’s intellectual contributions have got its idiosyncratic significance for the Hazara diaspora community, who usually find themselves at odds when confronted with questions that arise in the youths’ minds about their origin, history, culture and the causes that lead them to abandon their birthplaces. The History of Hazara Mughul answers their questions on who they are and what is their origin. Bisat-e Shatranj along with Qissa-hai-Natamam provide them with a perspective on socio-economic and political conditions which lead to the rise of militancy and consequently resulted in their persecution and migration.

The diaspora community and their friends have done whatever they could do to bring an end to the sufferings of the community members. However, their role, in particular, to raise the voice of their oppressed people in different International fora to make Pakistan accountable and force it to restore human rights for all ethnic and religious minorities cannot be ignored. Their contributions along with other peace loving people in Pakistan and across the globe will be a substantial help to return Changezi’s bygone Quetta back — a Quetta that was a happy little town filled with ethnic and religious harmony.

Note: The book is being translated into English and we recommend it to all our readers to get a copy when it is published.